Rethinking Language Around "Daycare" and "Quality"

Ivana Greco gives a good insight into what policymakers and writers who cover daycare miss when we talk about quality.

—> Quick note: if you like what you read, please consider liking, commenting or sharing this post. It helps this newsletter find new readers, and it’s free to do!

I don’t think there is a single parent in the world that doesn’t want their kid to have what we consider “quality” care. That care can come in many forms - by the parent themselves, friend or relative or hired person (“the nanny”) or in a formal setting like someone’s home or child care center. The latter has been dubbed “day care” by our colloquial English language, and yet “day care” often has its own heavy assumptions about what it is and what it does.

In the early 2000s, researchers began to realize that young children in child care weren’t just blobs but actually had rapidly developing brains that could sponge up information and form relationships and establish that je ne sais quai of social-emotional learning. When I was growing up, social-emotional learning wasn’t a term we discussed in school. Now, it’s everywhere: in schools, child cares, academic publications, and bestsellers in airport bookstores and blockbuster movies like Inside Out 2. The message, varying to some degrees, is that SEL skills are what kids can learn when they are young, and they can determine what allows one kid to succeed in life while another falters. It’s become our modern day marshmallow test.

The focus on SEL for young children comes at the same time we have an uptick in two-income families and single-heads of household seeking out care solutions for young children. Child cares (or daycares) aren’t merely a place to park your child between work hours - they can now become the ground floor of the SEL skills one needs to become kindergarten ready.

So this means we’ve become far more interested in defining quality in early care and education. And while the adage of what measures is what matters is true in education just as in any other industry, it also means we have some unusual ways to determine what quality care looks like. But care is not one of those things that a family can swap out as easily as an Amazon return or read a Wirecutter review and press “purchase”- it takes time and needs to fit within a family’s needs and budgets.

When I read this fantastic essay of

’s I asked if she would be open to my sharing it with readers of . I go out of my way to read Ivana’s work because (in addition to being a great person and writer) she also brings forth a viewpoint that isn’t always front and center in the care conversations: an Ivy League lawyer turned stay-at-home homeschooling parent, she reminds us that parents make all sorts of choices for what’s best for their families. And what makes sense for one family may be the opposite of what another one chooses. On paper Ivana and I may be opposites, but when it comes to digging into care policies we have a lot more common ground.Her essay is below. I highly recommend subscribing to her newsletter, The Home Front, as well.

Daycare: Let’s Talk about Quality

by

Before I start discussing daycare - which I’ve found to be a very sensitive topic - a fews disclaimers:

I am not anti-daycare. My older two sons were in daycare while I was working as an attorney. My oldest son started daycare at four months; my second son around seven months. I don’t think they were harmed by being in daycare. My younger two children are home with me, and while I enjoy spending the extra time with them, I would not hesitate to put them in daycare if family circumstances required.

This is not a post about policy proposals. I imagine my left-of-center readers will read this and have one set of policy ideas they like and my right-of-center readers will have another. Feel free to post your policy opinions in the comments, but that is not the point of this post.

This is also not a post about daycare before baby turns one, which I think has different considerations (and which I will address in a future post).

This is a post about how different daycares are different. Some daycares are great, some are good, some are bad, and a few (thankfully rare) are terrible.

With that extensive throat-clearing out of the way, onto the substance!

When discussing daycare, we hear often about the price. To give just one salient example, Zohran Mamdani — the front-runner mayoral candidate for New York City - has pledged to create a free, universal child care system. Daycare is certainly pricey. The Department of Labor maintains a National Database of Childcare Prices, which found that median price varies a lot, but is certainly high:

The price of childcare, to be sure, is very important. Quality also matters a lot. While quality is mentioned in debates surrounding childcare, questions about quality often play second-fiddle to the question of price. Why?

One reason may be that almost all parents believe that their daycare is high-quality. A 2016 study by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that 59% of parents believed their daycare to be excellent, and 29% thought it was very good. Only 12% of parents believed their daycare to be fair or poor.

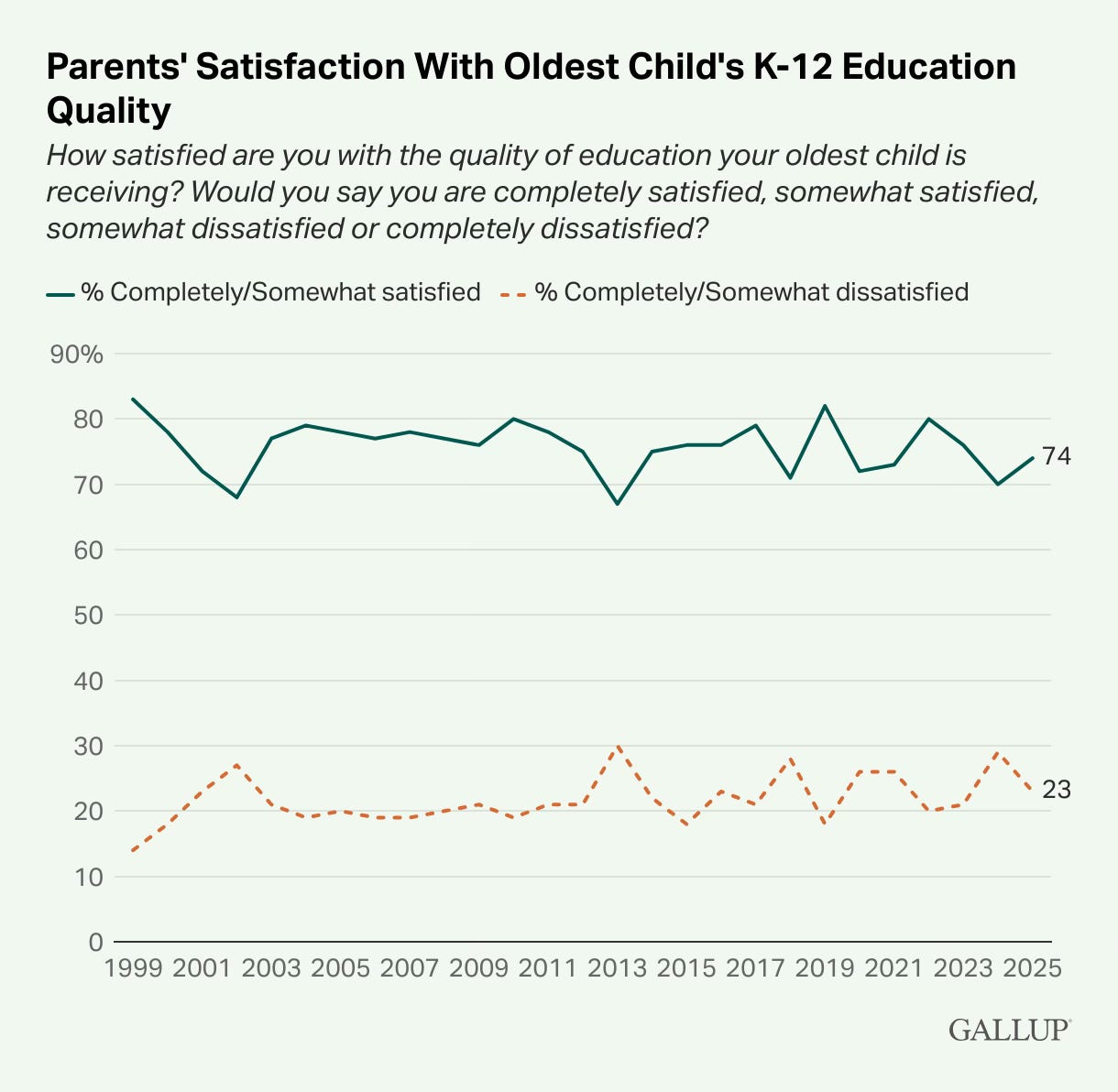

This, by the way, is similar to how parents view their local public schools. Most parents are satisfied with their own children’s education (even when they take a more pessimistic view of school quality generally!)

Unfortunately, many parents are wrong that their own children’s daycare is excellent, at least as experts measure the question. For example, one respected study found that only 11% of measured daycares were “excellent.”

A second reason that this topic is hard to discuss is that experts disagree on how to measure daycare quality. Rachel Cohen Booth at Vox has an excellent article on the topic titled: A critical fight over “quality” child care could shape millions of kids. In it, Booth explains that states have attempted to use a rating system for external childcare. The rating systems are known by the lengthy name/acronym — of course there’s an acronym — of Quality Rating and Improvement Systems, or QRIS. The following quote may give you a sense of the complexity of what these states are trying to measure:

These systems, which vary significantly across states, award ratings based on multiple dimensions, including teacher qualifications (such as holding a child development associate credential or a degree in early childhood education); learning environments (including safe teacher-to-child ratios, classroom cleanliness, and availability of age-appropriate books and toys); administrative practices (like documented emergency procedures and business management systems), and the caliber of child-adult interactions (measured through classroom observations).

It’s hard to know how the average parent understands these QRIS ratings (if they even know they exist). I did not know about the QRIS ratings when my kids were in daycare, and if I had, I’m not sure how seriously I would have taken them. Obviously I wanted my children to be in a safe and clean environment, but my main focus was on the “caliber of child-adult interactions,” or …. are the daycare teachers going to be nice to my kids??

In other words, it’s very hard to boil down daycare quality to a rubric. Much of it depends on fit: do the child and the caregiver match well? Is the environment well-suited to this particular child and this particular family? How flexible is the daycare around a specific child’s medical or behavioral complexities?

To give a couple of examples of how this plays out in real life, a Korean family that speaks Korean at home may prioritize a daycare provider that can speak to their toddler in Korean (or not: maybe the family is seeking early English language exposure in a daycare environment; it all depends!) A family with a toddler that they suspect will eventually be diagnosed with autism (autism is often not formally diagnosed until school-age, even if the signs may be present earlier) may find large group care to be profoundly challenging for their child.

A third reason we might be hesitant to discuss daycare quality is that it can be a very distressing issue. I’ve spoken above about how a lot of daycare quality depends on a match between provider and child … but there are also daycares out there which are simply unsafe. In providing some examples, I want to underline that daycare abuse is rare, and not something the average parent needs to worry about. However, it does happen. Here’s a snapshot of what Google news returns when I searched for “daycare abuse” while writing this post:

Picking one of the stories — and warning, this is graphic and disturbing - here is what one of the accusations included:

Police at the time asked [the witness] to reenact what she saw [the accused defendant do] using a doll. That video was shown to the jury after she described verbally what she witnessed.

“I was stunned, honestly, because I’m like, the way that was his body that just hit this thin piece of mat, and she had hit him so hard that his body ... excuse me,” Morris said while getting emotional. “His body had bounced enough ... that I could hear him wheezing for air. And I didn’t know what to do.”

This, obviously, is horrifying. Again, this kind of abuse is statistically very rare, but even once is clearly too much. How do we prevent this kind of abuse? There are a handful of tools: background checks, licensing, inspections, etc. But no system is ever going to be 100%, and that is always a difficult reality to face.

A fourth and final reason it is hard to address daycare quality issues is that it is often class-based, and Americans tend to shy away from discussing class issues. An upper-middle class family living in a wealthy, urban area with many childcare options to choose from is going to have a very different perspective than a working-class family in rural America that may only have one daycare center within a reasonable drive. For the former, the most relevant consideration may indeed be cost, since they have a number of good quality but expensive options to choose from. For the latter, cost is a big concern, but quality is also a big deal if the only local daycare provider isn’t good or isn’t a good match for their particular family. A family where both parents are working shift work jobs and risk getting fired if their toddler gets sick too many times …. and has to drop off a visibly ill child at a low-quality daycare … is probably going to have a very different perspective on ideal child care scenarios than two white-collar parents who have flexibility in working from home when their baby is sick.

Why does it matter? What’s the harm of focusing more on daycare price than on daycare quality? In a nutshell: I think that until we can openly and frankly discuss differing childcare quality, it’s going to be very hard to understand the stark divide between how different families view daycare. Think of questions like: is daycare harmful or helpful? What is the ideal family policy surrounding subsidies for daycare? Do parents want their kids in daycare or at home? How do we tailor childcare policy for specific regions and families? None of these can be answered — or even really tackled in a meaningful way — without a deep understanding of what good childcare looks like for different families, and how the quality of their local daycares affect them. Price is easier to discuss, because it’s objective. But without truly grappling with messy questions about daycare quality, we’re going to be left with only an incomplete understanding of how our fellow Americans understand childcare choices … to the detriment of both our social and political fabric.

Thank you again to for sharing her essay with readers of .

I'm a father and my daughter is now in her late teens, but I remember the same concerns from a decade and a half ago when she needed to be enrolled in daycare so my wife and I could both work after her grandfather, who had been caring for her during working hours, passed away.

The first place was a church, which got us through her potty training, but then shut down the program when she was three. Our second place was a home with an upgraded kitchen to meet state requirements, but well set up with a main playroom, a nap room and large fenced in backyard with a tree for shade and simple, homemade playground equipment.

The staff were local Hispanic and Pueblo women, who taught my daughter some simple Tewa and cooked traditional New Mexican dishes, which suited us perfectly, but might not have been a good fit for pickier parents insisting on restricted diets or a focus on learning numbers and letters.

We ended up moving to Nigeria, where my wife's family had lived before, shortly afterwards, and my kid began school in Abuja, but that's another story for another time.

Regarding costs, daycare is difficult to do well on the cheap. We were in Santa Fe, the state capital, and a wealthy city well staffed by government workers, so the quality was good in both of our choices, but neither was cheap. The cost was a factor in our move overseas, to be frank.

The most logical path I can see for Americans is extending the public school ages to include an early childhood component. If we want qualified staff we'll need to pay at what elementary schools offer.

Thank you for sharing this one!