When Head Start is Your Superpower

For Indigenous Communities, Head Start Programs are a Cultural Lifeline

It’s a gray day in May when I pull into the parking lot of the Walatowa Head Start Early Childhood Learning Center in Jemez, New Mexico. Signs along the way had informed me I was on sovereign land belonging to the tribe, signs that are more common in a place like New Mexico than they are in the Washington, D.C. area.

Have I been on tribal land before? (Aren’t we all on tribal land now?) Ages ago, I went to a Pueblo on a trip to New Mexico with my family. But connecting with tribal leaders wasn’t something I was familiar with; it had taken me many phone calls, several people vouching for me, and many rounds of emails to secure this meeting at Walatowa.

As a state, New Mexico has been investing in early childhood initiatives. This was notable, in a country where we invest less per child in early education than most of our peer nations, that this state was doing so on its own.

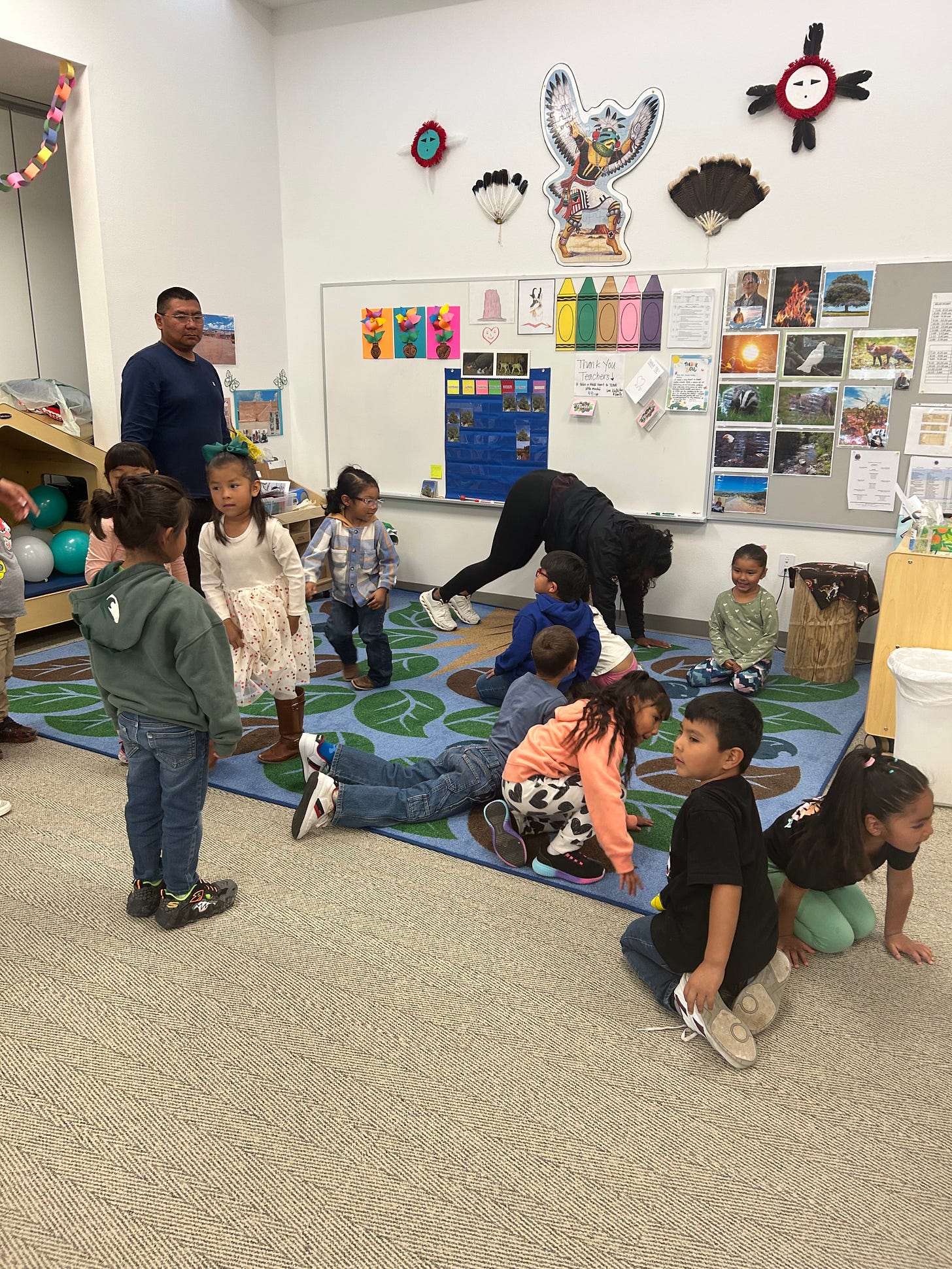

But researching this took me in another direction - was I aware that New Mexico was one of several states to have Head Start programs as a way to preserve indigenous language? Walatowa Head Start is one of these - conducted entirely in Hemish - the indigenous language of the Jemez. It’s designed to be a cultural lifeline for the kids who attend. Language is more than the words the children and teachers speak. It’s a way to be connected to a longstanding culture, one that many have not always had ready access to, and the customs, traditions and lessons that go along with it.

So at 9 a.m. each morning, the children line up outside, each with a small amount of cornmeal in their hands. Bertha Gachupin, one of the Head Start teachers, leads the children as they say their Indian name, the name of their clan, and then a prayer to learn and understand the Jemez language and have a good day at school, before blowing the cornmeal from their palms.

She invites me to come along to witness this. A child holds out the bowl of cornmeal and indicates I should take some. I do, blowing it out along with the kids.

When finished, they rub the remaining cornmeal dust over their hands and heart. “It gives them strength,” Bertha explains.

Cornmeal is sacred to the Jemez. Each classroom has a cast-iron grinder attached to a desk with baskets of corn next to it. Whenever it’s getting low, without even a reminder, children will go to the machine and start grinding it. Bertha selects a boy to come into the classroom to show this to me. He understands and starts cranking - it’s harder than it looks. But as he moves the handle, more cornmeal is added to the basket.

Of the 34 Head Start and Early Head Start programs in New Mexico, half are on tribal lands; Walatowa is one of three that are designed with formal language immersion programs in their curriculums (the other two are Saad K'idilyé Language Nest in Albuquerque and Keres Children’s Learning Center at Cochiti Pueblo). For tribal communities like Jemez, Head Start provides more than just child care and school readiness - it creates a lifeline to their cultural identity that generations have tried to take from them.

The person running the day-to-day operations at Walatowa is Lana Garcia, who grew up speaking the Hemish language with her mother and grandmother at home. But her school and reading were in English, and Lana went to college to major in English before becoming a teacher in a local public school system near Albuquerque. After moving back to Jemez, her daughter came home from school one day and demanded to know why she’d never been taught the tribal language. “It was painful when your own child asks you that,” Lana said. “There is no excuse in the world, I had thought myself that English was better.”

“The reality of language loss has really scared us,” said Lana. “Our language is really tied to our ceremony.” The school curriculum is filled with activities specific to Jemez: songs and traditional dances, elders who come in to do a story hour, and meals prepared and served on-site that come from tribal customs, like atole, a blue corn drink served hot, Jemez enchiladas, and frybread. The staff speak Hemish to one another and the entire time when they are working. When Lana answers a call in her office, she does so in Hemish, before switching to English when the caller is someone calling about an IT repair.

It’s not uncommon among tribes for a language to be oral-only, like Hemish, (which linguists also refer to as Hemish-Towa, or Towa). Lana explains that they don’t have permission to write Hemish, as it’s considered sacred.

Head Start is a federally funded program, which means decisions about its future are made in Washington, and not in Santa Fe. Though New Mexico has allocated significant funding for child care, including creating the country’s first Assistant Secretary for Native issues, it doesn’t have the capability to fund Head Start should the federal funding sources change. If Head Start funding is zeroed out, there is no back up plan to stay afloat. Lana explained that since Jemez is not a gaming tribe, they have no casino to collect revenue from and no spare funds that the tribal government could provide. Walatowa has also seen a drop in enrollment - before Covid they had 70 children, and now are at 57, and could face a decline in funding from Head Start for being under-enrolled.

But what Lana does have is a strong success record of keeping the Hemish language and culture alive. Some of the skills the children receive from watching and taking part in the ceremonies - such as having a longer, focused attention span - will help them throughout their education.

“When we watch our dances, it is all day,” said Lana. “You’re expected to sit and watch. Those expectations are given to us by the war captains that you stay for the whole day. You stay until the very end.” Lana recalls with pride at seeing several of her Head Start boys take a prominent singing role during a ceremony, and a child who insisted on going to the ceremony celebration on his own, even though his parents didn’t participate. He knew what to do, she explains, because he’d learned the traditions and customs here, at his school.

I recently published a story on Walatowa (of which some of this essay is adapted) and sent the final version to Lana once it was live. By now I’ve written dozens of stories on sensitive topics, where I’ve had to earn the trust of people who are not always accustomed to sharing their life story with a reporter. When I do, there is something of a final verdict that comes in when they see it live: Did I get it right?

It’s beautiful! Thank you!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Lana wrote back.

I don’t know what will happen with Head Start funding in this Administration - after claiming to zero it out, they did an about-face and are currently keeping it. I don’t know if Walatowa will be able to have more children attend so they can keep their existing level of funding. But I do know this is a story worth writing and sharing. It shows the power of early education, and the power of community and identity. And it shows the irrevocable proof of harnessing the power of early education to make a difference, for children, families and communities.

It shows the power of early education, and the power of community and identity. And it shows the irrevocable proof of harnessing the power of early education to make a difference, for children, families and communities.

A portion of this essay was adapted from this story, “For Some Tribal Communities, Head Start Programs Provide a Cultural Lifeline” published on The 74.

There's some reason for hope, as after next year our governor is likely to be indigenous herself: Deb Haaland, Biden's former Secretary of the Interior, is running in the 2026 election, and is favored to win.

Secretary Haaland is from Laguna Pueblo and has deep ties to her culture. I'm looking forward to voting for her.

If you're ever fortunate enough to visit, the Jemez people live in a beautiful mountain canyon with nearby hot springs, and both state and national monuments to their ancestors are worth exploring for those interested in learning about our first people.

Chaco Canyon isn't far away either, and is a stunning testament to the knowledge and capabilities of the indigenous people, showcasing the ruins of dozens of Great Houses, some with over 600 rooms, dating back a thousand or more years. The national monument is on tribal land (Navajo), but open to all. Many of the buildings are carefully aligned to the movements of the sun and stars, and the park has an archeo-astronomy program demonstrating these connections.

Unlike Barcelona or other European tourist destinations, where the locals are fed up with hordes of strangers pouring into their communities, tribes across New Mexico derive vital income from art, festivals, dances, and tours. They want and need business, and these jobs often allow tribal members to continue their ways, weaving rugs, forging silver and turquoise jewelry, making pottery in both traditional and new forms.

So please, visit and contribute. It's a beautiful state with wonderful nature: the Jemez and many other Pueblos are among forested mountains and river/stream valleys, so even in summer it's rarely scorching. Winter offers skiing at numerous peaks, some with operations run with tribal investments.