Who Needs a Safety Net Anyway?

A Q+A with author Jessica Calarco on the pub day of her new book (!) and my first ever GIVEAWAY!

Jessica Calarco’s book: Holding it Together, How Women Became America’s Safety Net, is out today - with the TL:DR version in today’s Q+A. (photo courtesy of Jessica Calarco).

I was on my way to a funeral - true story - when I made the spontaneous decision to pack Jessica Calarco’s book, “Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Safety Net,” to read on the plane. Maybe deep down I knew that it was going to be good. Maybe I’d had an inkling that it’s premise - that the United States relies on women to pick up the slack instead of creating a proper social safety net - was spot on.

Whatever it was, I read it all on that trip, typing notes into the Keep section of my iPhone to ask Jessica when I would interview her later. But I also knew that this book was both readable and relatable - something that other people would want to read. Especially people who care deeply about the way our country’s policies - or lack thereof - surrounding caregiving, parenting and support are designed. Rather than offering up my dog-eared advanced copy, Jess and her team have graciously provided a copy of Holding it Together for one lucky reader of

.Details at the end for how to enter.

But first, let’s talk about the book. Jess Calarco is onto something. There is a reason that women in this country feel that so much pressure rests on their shoulders, that parenting is hard, that too many expectations are heaped onto them, and that if they don’t hold everything together with pluck, grit, duct tape and super glue, that their worlds could fall apart.

The reason is because it’s true. Maybe not the part about the duct tape and super glue, but the reason so many women feel they must take on so much work and caregiving is that the United States does not have a robust social safety net the way many other industrialized countries do. We have no federal child care infrastructure and no federal paid family leave plan. We’ve skipped over the safety net chapter on how to run a country, and instead we rely on women to pick up the slack.

I had a chance to speak with Calarco after reading an advance copy and we spoke about everything from the outdated Supermom myth to the role humor plays in perpetuating misogynistic stereotypes.

The pandemic-era photo of the all-too-familiar juggle of writing/working with kids on zoom-school at Calarco’s house. Love that you can see the book draft and IU logo on the side of the screen (photo courtesy of Jessica Calarco)

A lightly edited and condensed Q+A is below, though a longer version is available over on

.Q. Your book talks about the United States’ insistence on maintaining the illusion of DIY society - that each of us should be making our own decisions and taking care of our problems without help from anyone else. But we know that many people actually need caregiving support at some point in their lives - why has this illusion endured for so long?

Jessica Calarco: This DIY society is beneficial for the billionaires and big corporations and their supporters who profit from maintaining this idea and the illusion that we don’t need a social safety net. Think of the big universal systems - child care, health care - they cost money. Who is paying the costs? We would be raising taxes on very wealthy people and corporations. That is threatening to people; it reduces social inequality in ways that manipulate the rest of us - exploitation. They have this interest in maintaining this illusion that we can get by without maintaining a social safety net. There is this belief that goes along with supporting the DIY model that not having a social safety net makes us safer because we are likely to make better choices without that safety net.

Q: Really?

Jess: Yes, this is the idea of neoliberalism economically. It originated in Austria in the 1930s and then was imported to the US for manufacturers to push back against New Deal policies. They were imported to the US and used to train economists like Milton Friedman, who then went on to shape policy for decades.

Q. So does this DIY model contribute to the way we value care, and why women are expected to make up the difference?

Jess: part of this gets back to the DIY model. If we don’t have a social safety net, like universal child care, universal health care, we still need those kinds of care. Within this kind of system, care work is too intensive to be profitable. This quickly becomes unsustainable, which means that it’s not ever going to be work within our profit-based economic system, without high levels of government investment, charging high costs to consumers, or exploiting people and paying too little for their work.

We have pushed the high labor intensive work disproportionately onto women, and you can see that in industries like child care, home health care, services, retail and house cleaning. And we push this onto people who are highly vulnerable - women, prisoners and immigrants.

Women hold 70 percent of the lowest wage jobs. The jobs held by women get further devalued over time. We treat care work as something that is somehow the moral or emotional benefits that must make up for what is not paid. So you have this system where women are earning far less than men do.

Q. You have an entire chapter devoted to this concept of “Good Choices Won’t Save Us.” Is the idea that if people made the right choices, they’d never have a need for a social safety net?

Jess: Yes, exactly. This gets back to the idea of the Neoliberal myth of the DIY society. Neoliberal economic theory states that societies are better off without a social safety net because if people don’t have a net to protect them from risk, they will be less likely to engage in risky behavior. The less protection you have, the better choice you make. You won’t need protection because you will have made choices instead. This has been fully debunked - a social safety net does protect people.

People are told, if you just make good choices, you will be fine: marriage, college, a STEM education, waiting to have kids. The appeal of that kind of mythology makes sense. In such a precarious world, it feels good to have a sense of agency. The problem is that correlation is not causation. The model that we have is based on the people who are able to make good choices. If someone is able to get married, buy a house, go to college and get a degree in a STEM field, they may have better outcomes but it most likely has to do with the fact that they had the privilege to make the decisions in the first place. It’s not that choices don’t matter, but we have to be cognizant of the level of privilege to make those choices that we equate with the path to success.

Q. What about childbirth? Plenty of people undergo all the risks involving gestating and birthing children, and have little control over those outcomes.

Jess: This is why this kind of model deeply ignores that there are risks that good choices can’t manage. [Whether] it’s childbirth, environmental risks with climate change, there are plenty of risks we can’t manage as individuals. This kind of messaging runs the risk of gaslighting people.

We see this with mothers and adverse outcomes in childbirth and child rearing. As if there is a right choice to make, and it’s your fault if you didn’t figure it out and make it.

Q. Let's talk about the sexism jokes. Your book explains that some men rely on humor to cover their own misogynistic tendencies, and you’ve posited that such humor actually makes things worse. Why is that?

Jess: These were two pieces that were surprising to me. When I talked to men about the inequalities in their lives they were quick to write it off as a joke. Even when they were making choices that looked deeply egalitarian, it was treated with a level of humor and a lack of seriousness.

I did a lot of reading and research on gender and sexism in the context of humor. Couching sexism in humor makes it more poisonous, because it becomes more palatable to men who can buy into the ideas without thinking of themselves as bad people. It also makes it harder for the women to push back. They’re told: ‘Stop being a nag. Can’t you lighten up?’

[This sexist humor] seems benign, though I would argue it can be deeply damaging. It is harder for women to push back in their context of the relationship and broader society that they are part of.

Q. Can you give an example?

Andrew Tate, he’s a former MMA fighter turned YouTuber, and already banned from a number of different platforms. There are hateful things that he says on many fronts. “Women should be men’s property in marriage” and that sort of thing. One of the problems with that is that if he is then able to write it off as a joke, it makes it harder for those who have been harmed by that rhetoric. It gives men an easier way to buy into the softer ideas by saying ‘at least I don’t believe the extreme version of it.’

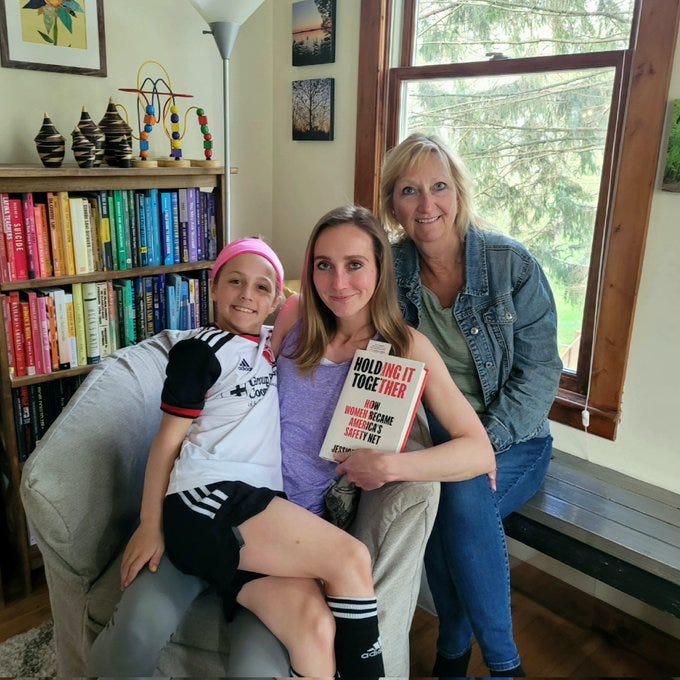

Calarco, her mom, her daughter and her book. Calarco writes about how her own mother shaped her perceptions of care and work, including the effort it took for her to run a childcare business of her own while selling Mary Kay cosmetics on the side, later going back to school to get her degree + masters. (photo courtesy of Jessica Calarco)

Q. When people read this book, and as you lay out all the concerns for the way we structure society so that an undue burden falls on women to act as the social safety net, what do you want the takeaway to be?

Jess: We have managed to maintain this illusion of a DIY society by pushing the risk and responsibilities onto women. Some women, often more privileged women, are able to push that risk onto other underprivileged women. But the engineers and profiteers of this system have managed to persuade enough of us to show that the system works - in ways that have made it incredibly hard for the safety net that we all need and deserve.

We need to be upfront about how a better social safety net could help to improve all of our lives - even if it reduces some of the inequalities between us. We need to move away from opportunity-hoarding, which in the context of that kind of precarity, we see that those in the most privileged position have an interest in pushing off the risk and responsibility onto others and improving their own lot. People are inclined to secure the resources to protect their own families even if it comes at the expense of others.

My hope is that by understanding this system, it can help to un-gaslight people by seeing where this DIY model comes from and how it’s hunting all of us, especially women. We need to demand a system that can work better for everyone, and reject some of the myths that tend to delude and divide us.

Jessica Calarco’s book is available for purchase here.

—> BOOK GIVEAWAY!

This book could be YOURS! Pictured on Jess’ Calarco’s rainbow-arranged bookshelves. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Calarco).

One lucky reader will win a copy of Jessica Calarco’s book “Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Safety Net.”

There are two ways to enter:

Become a paid subscriber! Paid subscribers help fund the research and reporting that go into this newsletter. All current paid subscribers are automatically entered, and anyone that signs up this week to become a paid subscriber will be entered TWICE!

Share this newsletter - post on social media (tag rebeccagalewriting on IG) or repost/stack on Substack.

If neither option works for you and you still want to enter, reply to this email about with your own story about work and care, and I’ll enter you as well.

Note: This giveaway is only valid for people with mailing addresses in the United States.

The winner will be announced in next week’s Substack.

Thanks so much for reading!

Can’t wait to read this, thanks for the sneak peek. I’m excited to hear more on the New America webinar in a few weeks too!

Thanks for this interview! I'm excited to get the book. If I don't win it, I'll buy it soon!